Correlation, causation and coincidence

Alternate title: Are you sure there’s fire at that smoke?

I’ve written previously about curse words for scientists. One term that I didn’t include, but probably should have, is “correlative”. It rates right up there with “data trend”. It boils down to someone telling you that sure, your data looks pretty, but it doesn’t mean anything. Which stinks to hear, even if it’s an important critique. Scientists strive for causation; definitively showing that A leads to B. Not that A and B are related because they occur together (ie: correlation) or randomly occur at the same time with no connection (coincidence).

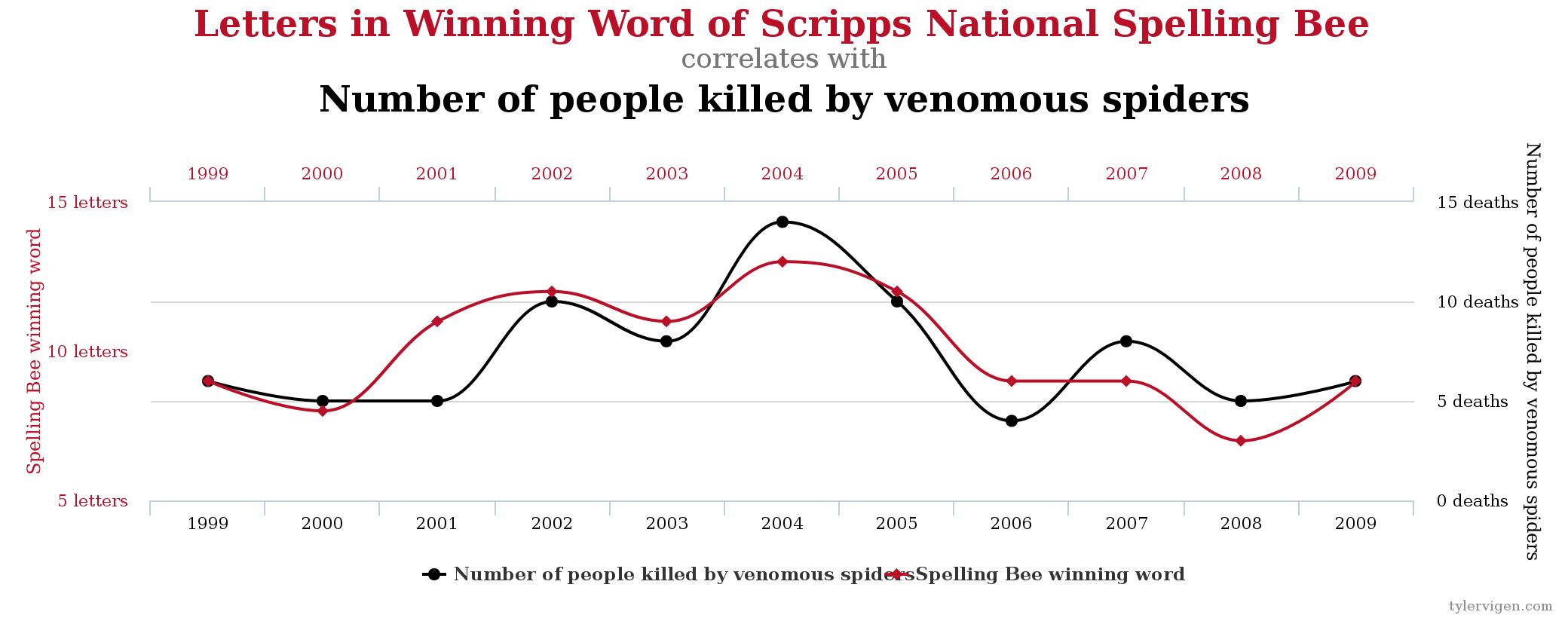

Or, to use a fun example from a wonderfully nonsensical website:

Image credit: Tyler Vigen

Image credit: Tyler Vigen

Clearly, this demonstrates that longer words in the Scripps National Spelling Bee angers venomous spiders, causing them to bite. I mean, that’s just common sense, right? Everyone knows that spiders become murderous when they feel their intelligence is threatened.

Seriously though, this example is pretty obvious in its ridiculousness, which is exactly why I’m using it. No one would call that anything except a coincidence, even if the incidences do correlate 80.57% of the time. That number means the data looks pretty, but doesn’t tell us anything about the underlying details.

So let’s say you run across a graph like this. Sure, the percent correlation is high, yet something just doesn’t quite sit right. What do you do to find out the truth? I’d start by looking at the timing.

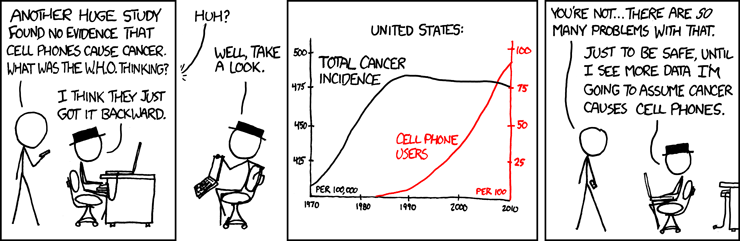

Image credit: xkcd.com

Image credit: xkcd.com

If event A triggers event B, then you’d expect A to happen before B. In our Spelling Bee example, there’s an increase in word length in 2001, followed by an increase in killer spiders in 2002. That could theoretically be the initiating event. Maybe spiders were totally fine with long words until something happened in 2001 that caused them to become murderous in later years when they heard long words. Or maybe that’s when spiders got cable and could start watching the program.

To test that hypothesis of causation, you need to run some experiments. I’d look more closely at the highly correlated time points (such as 2002, 2005 and 2009), maybe examining whether spiders killed more people in the days or weeks directly following the Spelling Bee. If you had access to spiders without cable, you could introduce them to a pre-recorded Spelling Bee (one group with a short winning word and another group with a long word) and measure anger levels. But until you test your theory with more in-depth studies, everyone just calm down! It’s only a correlation.

Another possibility is that the two factors (bites and word length) and in fact related, but not directly. There could be a third element at play that influences both separately.

This is a lot harder to figure out in studies, because you ultimately have to make an educated guess at what that factor is in order to test it. Maybe air humidity affects the ability of spelling bee participants to spell long words and it independently irritates spiders causing them to bite. How could you possibly figure that out just looking at the one graph? That’s the tough part of science and the reason a purely correlative study is not widely trusted.

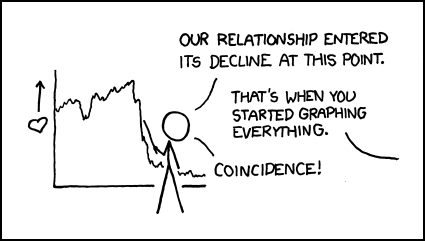

The final option is the one that makes me cringe: coincidence. It’s too easy to write data off as “coincidence” or artefact or even irrelevant. A lot of the time, it probably is. However, it can also mean that you’re ignoring data because it doesn’t fit your hypothesis and that’s where you can get into trouble in research.

Image credit: xkcd.com

Image credit: xkcd.com

Let’s look at a real world (and not crazy spider) example. One day you buy new shoes. The next day your feet hurt. Obviously, your new shoes are causing your foot pain, right? Causation. But what if it’s just correlation? Perhaps there’s a third factor, like you bought the new shoes to go on vacation where you were walking a lot more than normal. Sure, the new shoes might be causing the pain, but more likely it’s your increase in activity. Or maybe it’s pure coincidence! Maybe you didn’t realize you hurt your foot yesterday and that’s what’s causing the pain; completely independent of what shoes you wear.

I know this sort of thought experiment might seem unnecessary, but this is the basis of many medical decisions. People get a flu shot, then happen to catch a cold a day later and blame it on the vaccine. Or they use an alternative medical therapy that is supposed to cure a cold, and are happy when they feel better 3 days later (which is the normal time it takes to feel better, even when taking nothing). I’m not saying that alternative medicine has no benefit. I mean, I’ve published papers on probiotic use and I’m currently researching the benefits of black tea! What I want people to do is simply consider all the options. Don’t immediately assume that something is causative when it might be coincidental. And with that, I shall step off my high horse and take my leave. Good day sir!